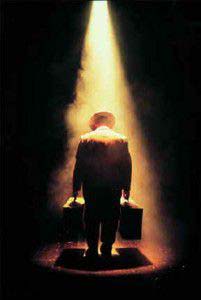

Anxiety, Regret and Persona in “Death of a Salesman”

I love theatre, and I’m lucky enough to live in the Toronto, Canada area. We have a lot of excellent theatre hereabouts, including the wonderful Soulpepper Theatre, which is not nearly so famous as it deserves. I was fortunate enough last Saturday to see Soulpepper’s production of Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman. which was arresting and raw. It’s a profoundly psychological play, in the ways in which it deals with anxiety, regret and “persona“, or the false self.

Lots of people know the story of Willy Loman, the crumbling salesman at the centre of the play, and the drama of his decline and eventual death. Clearly Willy is retreating more and more from reality and from life — but what pushes him into this?

Anxiety

Clearly, Willy and his family live in an atmosphere of intense anxiety. In the initial scenes of Act 1, Willy has returned from a business trip because he cannot concentrate when driving, and has nearly driven off the road. The interactions between Linda and Willy are full of an unacknowledged but agonizing anxiety that pervades the whole of the play until the tragic climax. An important psychological question, though, is, “What is the source of this anxiety?”

Grandiosity and Failure

I believe the answer is found in the tension between Willy’s grandiose and idealized image of greatness, and his own very real sense of failure to live up to this idealized image of himself, to be the “well-liked” man whose fame precedes him, and for whom all doors open. Willy does not dare become fully conscious of this profound sense of failure. He can only look at it indirectly, or acknowledge it glancingly in his interactions with Linda. It seems when he does do this, he expects to be re-assured by Linda, to be argued out of his feeling. Right through the play Linda enables Willy by shoring up his illusions.

Willy’s Persona

In Jungian terms, Willy is firmly in the grips of a persona (Latin for “mask”) or false self with which he identifies and tries to present outwardly to the world. But it is deeply at odds with who he really is, and his attempts to carry off this masquerade are costing him more and more emotionally and — dare we say it — spiritually. Willy is in a horrible dilemma: the only image he has of himself is as a “well-liked” salesman — and yet he knows that he has failed profoundly in realizing this ideal. However, there is no other sense of himself that he can find to hang onto, and so he is drowning.

Biff

So Willy does what parents often do in this kind of situation: he transfers all of his hopes for success and greatness to his sons, and in particular, onto his eldest son, Biff. However, whatever wounds Biff may be dealing with, he cannot ultimately bring himself to live out the unlived life and fantasies of his father. After initially succumbing to his father’s illusory picture, Biff refuses to enable his father further, saying “we’re a dime a dozen, you and I!” to Willy, which is the very thing that Willy cannot, will not accept.

Regret

The picture is further complicated for Willy by his profound regret, particularly for an incident in which he was discovered by Biff with another woman with whom he was having an affair in a hotel room. This incident has a profound and fateful effect on Biff. Miller’s dialogue masterfully shows how Willy can neither really face and be honest with himself for what he has done, nor can he release himself from the torture of his regret. Finally, this regret will lead Willy to a horrific act of atonement, which is intended to restore Biff to the path of “greatness” — as imaged by Willy.

“The Woods are Burning”

What is it to be consumed by false self, by persona? What are its inner psychological effects? I believe that playwright Arthur Miller captures this powerfully in one phrase that Willy uses several times throughout the play: “the woods are burning!” In dreamwork and in fairy tales, the deep woods, which are dark and where one’s view is limited, are often the image of the unconscious. The image of the woods burning, of a huge forest fire in the unconscious symbolizes the psychological reality in a profoundly eloquent way. The true self may be ignorred, and may be pushed into the unconscious, but not without powerful, often devastating consequences.

What about You and I?

The false persona and false self are real things in human life, not just art. It can be a devastating thing to live with a false sense of who one is, and without any real connection to the true self. I have had personal experience with the ways in which such an over-identification with the persona can bring a person into difficulties. I was fortunate to have the help of a good case studies to get me through that extremely difficult period.

Staying as true to the real self as possible is an ongoing process in life, a genuine psychological work. This is especially true in a society like ours, which becomes more success and image-oriented with every year, or so it seems. Are these issues which you, too, have encountered in your life, or are addressing right now?

1-905-337-3946